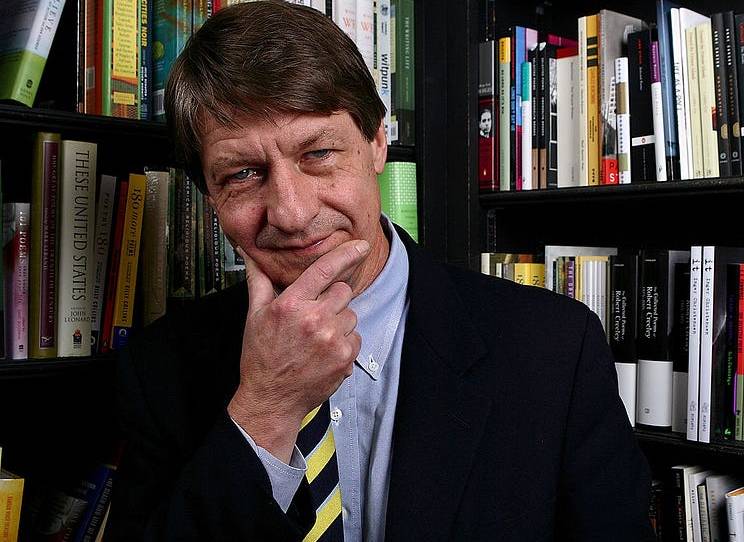

P.J. O’Rourke, Humor, and Wisdom

Dear Reader (including all the people who think San Francisco is overrun with white supremacists who care deeply about school board elections),

I feel a little bit like Kris Kringle, seasonal employee of Macy’s, sending kids and their deep-pocketed parents to Gimbels to get the quality goods. But I just don’t really have it in me to write a whole piece about P.J. O’Rourke and, even if I did, I couldn’t hold a candle to Matt Labash’s piece which is thankfully more tribute than eulogy or obituary. John Podhoretz’s quickfire column on P.J.’s passing is also worth reading. As are several others.

I knew P.J. a little and I admired him a lot. At times I envied him, but never in the resentful way we do when people have undeserved success. P.J.’s success was entirely deserved—if anything he was undervalued. Writerly envy of other writers is very common, in part because even though we know better, we can’t help but suspect that the good stuff comes easier for them than it does for us.

But we weren’t friends. At best we were friendly acquaintances. I treasure the handful of times I got to drink with him or talk to him or—most of all—listen to him. But I don’t have stories that can hold a candle to anything Pod or Labash can muster, and there’s no point in trying. Moreover, I’m not an O’Rourke completist, and I don’t want to pretend otherwise. In short, there are others who can write better and more with more knowledge about his talents. And more importantly, readers don’t need anybody to tell them what they already know: He was supremely talented. The proof was in the pudding, like your wife’s missing engagement ring.

This much I can tell you from my lived experience and from what I know from mutual friends: P.J. O’Rourke was a truly decent guy who (in accordance with his philosophy) treated everyone he met with dignity. He was someone who (in accordance with his midwestern upbringing) assumed everyone had every bit as much of a right to extract their share of oxygen from this world and convert it into an opinion. Whether he thought their opinion was worth the exchange rate is a different matter.

As I’ve said on a few podcasts now, in some ways P.J. was a cautionary tale for me. There was a time when I was encouraged to be “the next P.J. O’Rourke”—despite the fact that he was more talented than I could ever be. Moreover, P.J. was smarter, more informed, and more philosophically sophisticated than an enormous number of self-serious public intellectuals who have never produced an original thought over the course of their careers. Sure, they know some Latin or Greek and can throw around some quotes. But … meh.

P.J. not only knew what he believed, he knew why he believed it, and he could make it all a hooker-and-cocaine party at Jimmy Caan’s Malibu pad for the reader. So why not try to be like that guy?

Well, first, because it was too damn hard. Writing funny all of the time is like trying to keep as many Cheetos in your mouth as will fit while going about your regular business. You can do it for a while, but eventually you’re gonna spew something in public nobody wants to see.

Second, because P.J. never got the respect he deserved. Or to be more precise, he never got the kind of respect he deserved. Writers respected him, because we knew how hard it is to go your whole life with a mouthful of Cheetos and never once spray the reader with Agent Orange. OK, I need a better metaphor, but you get me.

The point is he didn’t get the respect he deserved as an original thinker and intellectual—because he was “just” a “humorist.” That realization turned me off to the idea, like a fat bagpiper in a kilt posing like Marilyn Monroe over a street grate. It wasn’t just that it would be hard. It would be something close to a permanent commitment. Getting a reputation as a humorist is like getting a permanent tattoo. Sure, it can be removed, but it’s painful, no fun to watch, and leaves a scar.

Good humor.

Anyway, rather than run through all the smart and insightful things P.J. didn’t get enough credit for—my plane’s Wi-Fi is as reliable as a coin-operated dialysis machine and I didn’t bring his books with me—let me offer a brief intellectual defense of humor. (I once seriously considered doing my senior thesis in college on the philosophy of laughter before I came to my senses.)

Philosophers have always had a problem with humor.

Plato thought laughter was dangerous and uncouth. If he had his druthers, there’d have been “No Laughing!” signs all over the Republic. He actually panned the parts of the Odyssey and Iliad that said there were a lot of yuck-yucks in Mt. Olympus. Serious men don’t laugh hard so gods certainly shouldn’t, Plato bitched like a guy who couldn’t tell a joke. The medieval Christian philosophers were also pretty down on humor. I like imagining a comedian leaving a monastery and saying, “Worst gig ever.” Some of this is understandable because the Bible doesn’t always cast laughing in a positive light.

Also, from Plato onwards, a lot of philosophers defined laughter in the most, well, dickish light possible—laughing at other people’s misfortune or mistakes. Laughter, Hobbes wrote, expresses “a sudden glory arising from some conception of some eminency in ourselves, by comparison with the infirmity of others, or with our own formerly.”

Things started to improve, if memory serves, with Kierkegaard whose little-known tract “Ten Reasons You Should Pull My Finger” broke new ground. I kid. I kid.

But Kierkegaard and Kant had more nuanced views of humor, seeing it as an effort to illuminate the incongruities and inconsistencies—even the absurdities—of existence. (This shouldn’t be surprising, because as Mel Brooks explained, “K” is the funniest sound so it only makes sense that the philosophers that begin with K should get it).

And that’s why I like to think the philosophers didn’t like funny men: It’s competition. Philosophy spends a lot of time trying to reconcile apparent contradictions and incongruities in all sorts of very serious ways. Comedy doesn’t necessarily try to reconcile the weird contradictions of existence, but it’s really good at pointing them out. Many versions of the “relief theory” of comedy make this point. There are all sorts of weird glitches in the programming of existence—or in the programming that governs how we perceive existence. We don’t always consciously think about them, but when a comedian points them out—“Did you ever notice …”—the recognition of the glitch brings us relief or release, say folks like Freund and Kant. I think there’s some truth to that, but I also think there’s a special feeling of joy and affirmation that comes when we laugh, particularly in groups. It reminds us we are not alone in our bewilderment, confusion, unease, fear, or contempt. Some kinds of laughter amount to saying “Shweeooo! I’m not the only one!”

It takes a lot of chutzpah for eggheads like Plato to crap on comedy as the stuff of false superiority. Philosophers are the ones who want to be de facto mystics demystifying the universe to everyone, often in ways no one can understand. Comedians do something similar, and all it takes is a two-drink minimum (unless you’re Socrates).

Obviously, P.J.’s passing put this stuff in my head, but I made a similar point when my dad, one of the funniest and wisest people I ever knew, died:

… But I think it would be a mistake to think my Dad’s wisdom and his humor were different facets of his personality. For him, “humor” and “wisdom” were different words for the same thing. After all, a sense of humor is merely the ability to see connections between things we haven’t noticed before (while laughter is what we do when we realize that those connections should have been obvious all along). Is wisdom really such a different thing?

Now, I don’t think wisdom and humor are synonymous terms in all circumstances. But I do think they are deeply related in ways that matter. Wisdom is to knowledge what knowledge is to information. Wisdom grasps the reality of a particular situation and how it both conforms to and departs from both the norm and the ideal. The norm is how things actually work, the ideal is how they’re supposed to work, and pointing out the difference defines a huge swath of stand-up comedy and funny writing alike.

Of course, satire is not the same thing as comedy, and P.J. was far more of a satirist than he was a comedian. But both depend on careful observation of the world as it is. Satirical writing, by definition, is writing intended to ridicule. That’s why the only good satirical writing is both truthful and aimed at those who deserve it. This is why virtually every good memoir of life under communism often feels like satire even when it’s just truth-telling. Solzhenitsyn did not fancy himself a satirist, but telling the truth about the absurd is an act of satire, whether intended or not.

That’s what P.J. O’Rourke did. He saw the absurdities in our politics and culture—large and small—and told the truth about them in terms we could relate to. It was called humor. But it was a hell of a lot more.

Various & Sundry

Canine update: The girls are staying with Kirsten while we go off to visit my daughter at school. It takes so much stress out of the equation when we know the girls are with their favorite “aunt.” Things have generally been good, although Pippa really didn’t like going to the beauty salon, and she really liked leaving. You gotta admit, she looks good. (Zoë —who never goes to the groomers, which is why you don’t see many one-armed dog groomers —looks good too.) Meanwhile, Chester has been coming around a lot more often. He even violated the rear perimeter, which created an opportunity for this iconic photo. Anyway, we’ll miss the beasts but we’ve also missed Lucy— a lot. And we can’t wait to see her.

ICYMI

Get happy with last weekend’s Ruminant

In defiance of the Egg Council, Tevi Troy returns to The Remnant

What the Ottawa protests reveal about our political dysfunction

GLoP pays tribute to Ivan Reitman and P.J. O’Rourke

The Remnant with Andrew Egger on the Durham probe

And now, the weird stuff